I’ve done it! I have finally made the trip, all sixty minutes of it, to Jane Austen’s house in Chawton. After much hesitation, my sister and I visited it a few weeks ago. I say, hesitation because I was afraid that I’d arrive at the house only to find that its sense of history and therefore romance had been replaced by scheduled tours and improbable illusions set up to appease the masses. But I needn’t have worried. Our entire afternoon felt like we’d been whisked back in time, similar to what happens to my heroine, Beth Goldsworthy in Becoming Lady Beth.

Jane Austen lived in Chawton from 1809 until near her death in July 1817. In 1809, her brother Edward Knight had been recently widowed and with eleven children to care for, he offered Mrs. Austen and his sisters, Jane and Cassandra, Chawton House so that they may help him out. It was whilst living in Chawton that some of Jane’s greatest works were published: Sense & Sensibility and ‘First Impressions’ renamed as Pride & Prejudice. She wrote Mansfield Park there in 1812, completed Emma and started Persuasion in 1815 and wrote the first twelve chapters of Sandition in 1817 but did not finish due to her developing illness. These books were very favourably received by the public and even caught the attention of the Prince Regent.

Chawton, as a village, still retains that picture-postcard Englishness. Standing in the village grounds, it feels like you are transported back in time. The houses have maintained that old charm; their facades are all crooked brick, uneven roof tile, trailing wisteria and crawling rose bushes. The setting has held onto time so well that I don’t think any visitors would be surprised if suddenly there were horses and carriages filling the roads, rather than cars.

Jane Austen’s donkey cart which she mentions in her letters as a means to get around especially when her illness struck.

Our first stop when we reached Chawton was to visit Cassandra’s tea rooms. I would say, that we had come across all old-english and that we were in need of ‘refreshment’ but in fairness we simply could not bypass such a pretty little teashop with such lovely staff. It was worth stopping for tea, if only to appreciate the collection of dainty teacups hanging from the shop’s ceiling. Fortified, we went straight to Jane Austen’s house. I joked with a kind lady at the museum shop, saying that I felt a little under-dressed for the occasion and she informed me, with all seriousness, that there were regency outfits at the ready for us to wear. Guys, I was so excited I nearly fell over myself trying to get to them. Gowned up we took our time investigating the house.

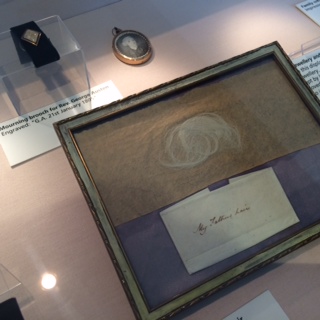

Jane Austen’s House may have had quite a few facelifts over the years but it retains much of the shape it would have had when Jane lived there. Notable layout changes were that the original front entrance of the house had been walled off and is now a small alcove with a fireplace. Being a Saturday, there were many other tourists visiting the house. So it was busy but as other visitors will discover, the atmosphere within is so striking that it does not matter. Tourists are moved to speaking in a respectful whisper as they work humbly through the numerous rooms. In almost all the rooms, there are copies of paintings done by and of the Austens’ or relatives thereof. You can see clearly the family resemblance between the generations. The Austens all seem to share a similar ruddiness to their cheeks and a similar beguiling, wide-eyed gaze. In one of the rooms, there is display cabinet containing mourning broaches and framed locks of hair, namely from family members, including one showing a thick white curl from George Austen (Jane’s father).

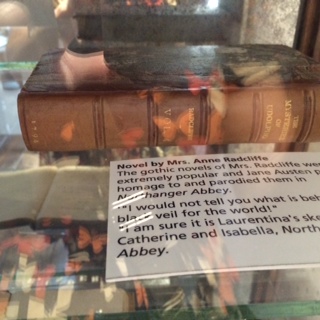

Copy of The Mysteries of Udolpho. Popular reading between Cassandra and Jane at the time. Must dig my copy out!

Some of Jane’s or Cassandra’s letters are possible to view and also pages from some of Jane’s manuscripts. It is frightening how little editing Jane had to do to her work. As a writer this was a hugely intimidating discovery. I have often wondered about how frustrating it must have been long ago for novelists, all that writing and rewriting using only pen and paper. Paper was relatively expensive and Jane did not have access to a word processor. It was pen and ink all the way, page after page. The thought of editing turns most modern writers’ blood cold but back then rewriting must have been a painstaking process. However, after looking over her pages, there is barely a word changed from her original draft to final. And so the problem is overcome. Just write perfectly from the beginning and there will no need to rewrite. Impossible talent, right? Not for Austen.

As you move through the house, you find yourself feeling increasingly sad about how tragic it was that such a talent died so young. Just before you enter Jane’s bedroom, there is a segment of the wall that showcases Cassandra’s letter to their niece detailing Jane’s final days and the particulars of her illness up to her death. Throughout reading it, you experience that growing sense of helplessness that we all feel when listening to or seeing an immense talent living out what we know are their final days. How many more books could she have completed in her lifetime if the mystery illness she was plagued with did not strike her down? I found it particularly poignant that her illness was and still is undiagnosed. If they had discovered what was troubling her could she have been saved? In this, Austen remains, ever the author by leaving us permanently asking that age-old question: What if?